The History of Liechtenstein: A Very Brief Sketch

Photo by Henrique Ferreira on Unsplash

In the last article I described the uniqueness of Liechtenstein’s constitution. In this one I want to sketch out a very brief historical overview of the Principality. As a sketch it is not aiming to be comprehensive in any way but rather just outline some of the main events and themes in Liechtenstein’s history with a few interesting snapshots sprinkled in too. This blog is premised on the idea that understanding the past is vital to understanding the present, so if we are to understand the uniqueness of Liechtenstein’s monarchy and constitution today we need to place it in its proper context.

From the Middle Ages to 1800: The growth of the Liechtenstein family

Although the Liechtenstein family can trace itself back twenty-five generations, the Principality that bears its name is much younger. The first Liechtenstein on record, Hugo von Liechtenstein built a castle just south of Vienna between 1130 and 1135 on light, chalky rock, or ‘lichter stein’. The family lost hold of it in the late fourteenth century (although they did re-acquire it in the early nineteenth century). Subsequent generations of Liechtensteins acquired various lands throughout the Middle Ages in both Lower Austria and Moravia. As David Beattie, former British ambassador to Switzerland and Liechtenstein, writes in his biography of Prince Hans-Adam II:

From these beginnings can be discerned three threads which were to run through the family’s whole future history: tenacity in protecting and expanding the family’s assets; a strong involvement in politics, strategy, and diplomacy; and an invited presence in what is now the Czech Republic that was to last for seven hundred years.

From the late thirteenth century on, the Liechtensteins opted to align themselves with the rising Habsburg dynasty, an alliance which, while not always smooth, was to prove highly fortuitous in the long run. Following 1517 and the Reformation, the Liechtenstein family, like many central European nobility, adopted Protestantism. This put them somewhat at odds with the Habsburgs, yet because of the family’s strong territorial position in Moravia, the Habsburgs could not afford to be too confrontational. Likewise, the Liechtenstein family took care to cultivate good relations with the Habsburgs. By the following century, however, the family had re-converted to the Roman Catholic Church. It was during the seventeenth century that the family grew in prestige. In reward for services rendered, Karl von Liechtenstein was raised to princely status by the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II in 1621. The following year he was made Viceroy of Bohemia and became a Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, the first of his family to receive the honour. In 1623 he was made Duke of Jägerndorf.

Prince Karl I (1569-1627)

His successor, Karl Eusebius (1611-1684), was the first prince of the family to collect art, something which has remained an important aspect of the family’s activities to this day. It was, however, under Hans Adam I (1657-1712) that the modern state of Liechtenstein began to take on recognisable shape. He expanded the family’s art collections and constructed the City Palace in Vienna as well as the nearby Garden Palace. In 1699 Hans-Adam I had purchased the Lordship of Schellenberg (outbidding the Bishop of Chur) and then in 1712, the County of Vaduz. After the completion of the latter and the reunification of the two territories under one ownership, Hans-Adam I died.

Johann I and national sovereignty

Prince Johann I (1760-1836)

The next significant watershed occurred in the early 1800s against the backdrop of the Napoleonic wars. During this period, Liechtenstein was ruled by a figure of significant renown: Johann I (1760-1836), one of the leading military commanders of his age who saw action in the Austrian-Ottoman War of 1788-91 and during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars in the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Austria. He was noted for his personal courage on the field and a series of very narrow escapes which somehow never seriously wounded him. Liechtenstein obtained full sovereignty in 1806 through a strange turn of events. Napoleon had decisively defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805. The following year, Emperor Francis II abdicated and, after 960 years of its existence, dissolved the Holy Roman Empire. Napoleon then reorganised many of the Empire’s former states into the Confederation of the Rhine, which Liechtenstein then joined. For the first time, its prince no longer owed any feudal obligations to an overlord and the Principality became effectively independent. The Confederation of the Rhine itself was dissolved in 1813, but Liechtenstein joined the new German Confederation in 1815, of which it would remain a member until 1866.

In 1818, Johann granted Liechtenstein a constitution but it was absolute. There was a parliament, but there were only two two estates: the clergy and the peasantry. This was also the year when Johann’s successor, Alois Joseph became the first ever member of the Princely Family to actually visit the Principality. As Prince, Alois II aligned Liechtenstein closely with their eastern neighbours, Austria, cemented through a customs and taxation agreement in 1852. These close ties, manifest among other things in the use of Austrian weights and measures and currency, would remain until the end of the First World War and the collapse of the Austrian monarchy.

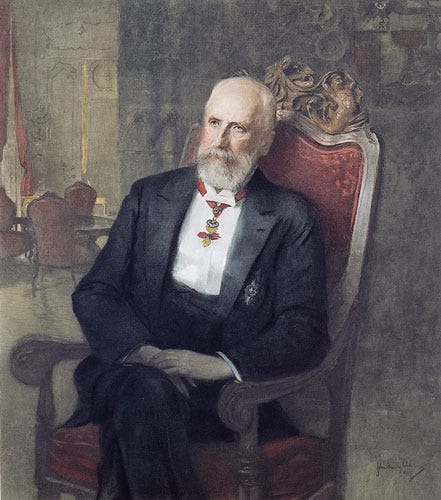

Johan II and the 1862 constitution

Prince Johann II (1840-1929)

The next major constitutional moment arrived in 1862 under the reign of Johann II, son of Alois II. The new constitution vested sovereignty in the Prince who alone had the power to summon or dissolve parliament, appoint or dismiss officials and represent the nation internationally. He had to pledge to rule in accordance with the constitution and laws of the Principality. Parliament, on the other hand, had the unlimited right to propose legislation and had to approve direct and indirect taxes and levies as well as the budget. Suffrage was extended to any male over 24 years old and voting was compulsory. For the first time, the constitution guaranteed the rights of personal freedom, freedom of religion, habeas corpus, the right of complaint and petition, assembly and freedom from arbitrary house search. Johann II was an immensely popular monarch and under his reign there was considerable material progress and modernisation. More widely, one problem that emerged was the question of international recognition. As a member of the German Confederation since 1815, Liechtenstein had attained sovereign status in addition to a number of rights and duties, such as the obligation to provide a military contingent (of 82 soldiers). Prussian victory in the Austro-Prussian War brought the Confederation to an end. Liechtenstein ended its military service. The last expedition of these soldiers does provide a curious anecdote. Having left the Principality on 26 July 1866 the contingent returned in September with an extra member—an Italian solider looking for work.

The First World War and the 1921 constitution

When the First World War broke out, Liechtenstein remained neutral rather than ally itself with Austria. Unfortunately, because Liechtenstein fell under the Austro-Hungarian government’s postal censorship, the Entente powers viewed the Principality as being under enemy control and applied economic sanctions. When the war came to an end, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy collapsed. The days of Liechtenstein’s close relationship with Austria were at an end. Thereafter, it came to be closely aligned with its western neighbour, neutral Switzerland. There was significant internal change brewing within Liechtenstein too. In 1921, after years of political tension and debate over the role played by Austrian governors within Liechtenstein politics, at the expense of native National Councillors, the Principality once again introduced a new constitution. The spearhead of the opposition had been the lawyer Dr Wilhelm Beck (1885-1936), founder of the Progressive Citizens’ Party, who campaigned under the slogan ‘Liechtenstein for Liechtensteiners’. Affection for the monarchy as an institution was widespread, and Johann II had been a popular prince, so there was never any meaningful republican sentiment, let alone movement. The new constitution made a number of important changes. All members of parliament were now to be elected by the people, who also acquired the right to convene or dissolve parliament by popular vote. Parliament now proposed members of the government, all of whom had to be native-born Liechtensteiners, to the prince. The people also acquired the right to introduce, repeal or amend laws by referendum as well as propose amendments to the constitution. This direct democratic element was of course greatly influenced by the long-held practices in Swiss democracy and reflect the changing political orientation of Liechtenstein away from Austria towards Switzerland.

Towards the Second World War

The interwar period was of course greatly unsettled. Liechtenstein had failed to gain a seat at the League of Nations, something the Princely House had deemed necessary to establish and cement the Principality’s sovereign status amid a turbulent period of political unrest and rapidly shifting boundaries and allegiances. Meanwhile, the princely properties in Bohemia were under severe threat from the Provisional Czechoslovak Government whose Land Control Act of 1919 abolished aristocratic titles and privileges and distributed the large estates to small farmers. For Czech nationalists, Liechtenstein properties represented an unfortunate legacy of historical injustice extending back to the tumults of 1620. In reality, much of the Princely House’s property by far predated the Thirty Years War since the family had maintained a presence in Bohemia and Moravia since the Middle Ages. The Czechs, under Edvard Beneš, treated the prince as an Austrian citizen and refused to recognise his sovereignty over the Bohemian properties. Compensation was given but the loss of these properties represented a serious decline in income for the Princely House. This rather drawn-out process eventually interrupted by the German occupation of the Sudetenland in 1938, something which would also end up having long-term ramifications for the Princely House’s properties.

Although Liechtenstein had adopted a policy of neutrality, it was by no means unaffected by the gathering storm clouds of the 1930s. In geopolitical terms, its position as a Germanic land so close to Nazi Germany rendered it precarious. It had no means of defence of its own, relying on Switzerland. Later, during the war itself, the Swiss, under the military command of General Henri Guisan, had mobilised all their defences against a possible Axis invasion. In that event (a scenario which has been hotly debated), there would be little chance that they would be able to aid Liechtenstein. The Principality’s shared border with Austria was also a concern, especially given the Anschluss of 1938. On the other hand, tiny Liechtenstein had little strategic value for Germany. It was a cause for irritation for Hitler though, no doubt exacerbated by the fact that Franz I, Prince of Liechtenstein between 1929 and 1938, had a Jewish wife, Princess Elsa. Within the Principality itself, there was a vociferous minority who agitated for union with Nazi Germany, organised under the VDBL (Volkdeutsche Bewegung in Liechtenstein, or, German National Movement in Liechtenstein). In March 1939 they staged a rather shoddy attempt at a coup, a desperate attempt to draw help from Nazi forces over the border in Austria. The putsch was defeated by angry locals and served only to bolster loyalism within Liechtenstein and a wave of patriotic feeling. It also went against Hitler’s policy towards Liechtenstein. Prince Franz-Josef II had visited Hitler in at the beginning of March 1939 and had received assurance that Germany had no interest in challenging Liechtenstein’s independence. The situation was to remain that way.

The close of the war did bring about an unusual situation. In early May 1945 a band of several hundred men and some women of the First Russian National Army, anti-communists who had served with the Wehrmacht, arrived in Liechtenstein seeking refuge. Every other country to which these Russians had fled at the end of the war (including Britain) had send them back to the Soviet Union where they were either imprisoned in gulags or executed. Liechtenstein took many in (some were persuaded under false pretences to return to Russia by a Soviet delegation). Those who stayed eventually made their way to Argentina.

The postwar period

The ongoing interwar saga over the land reforms in Czechoslovakia appeared to have been brought to an end by summer 1938 when Czechoslovakia recognised Liechtenstein and President Beneš congratulated Prince Franz Josef on his accession. However, this state of affairs was violently interrupted by the Munich Agreement and the cession of Sudetenland to Germany. There were ongoing disagreements over the value of the Princely House’s confiscated properties. By the end of the war, however, the prospects looked even worse as Beneš confiscated it all, along with all property belonging to the Czechoslovak Germans. Aside from the sense of personal loss, these confiscations had a profoundly damaging effect on the finances of the Princely House. Very soon it was reduced to selling off parts of its extensive art collection in order to avoid bankruptcy.

Prince Franz-Josef II (1906-1989)

Economic development had been central to the politics of Liechtenstein since the 1920s but it was since the Second World War that the growth in prosperity became internationally noticeable. This was achievable through low taxation rates and regulations and strong private property laws. The dire state of the Princely House’s finances, however, required serious attention. The reversal of this state of affairs and the transformation of the Liechtenstein monarchy into the secure and highly prosperous institution of today can in large part be attributed to the present Prince Hans-Adam II. Although he didn’t become the reigning prince until his father’s death in 1989, he had been exercising the day to day official duties as Hereditary Prince since 1984. Going back even further, however, it is clear that resolving the family’s financial issues had been high on his agenda since his youth. His father, Franz-Josef, had discouraged him from studying his preferred subject of archaeology at university on the grounds that a business and economics degree would be more useful to him as future prince (he graduated from the University of St Gallen in 1969 with a Licentiate in Business and Economic Studies).

During the 1970s, Prince Hans-Adam set about restoring the Princely House’s finances, focussing efforts on the family bank (now LGT Bank AG) and the family businesses in Austria. He also began the work that would engage him for the next few decades—restoring the balance of the constitution and establishing and cementing Liechtenstein’s position internationally. In early speeches he spoke about how Liechtenstein used to be carried on the ‘broad back’ of the Austro-Hungarian Empire before sliding off into ‘Switzerland’s comfortable rucksack’. But Prince Hans-Adam felt that membership in wider international organisations was necessary in order for Liechtenstein to be more properly recognised as sovereign and independent. Public opinion in was strongly opposed to membership in the UN for a number of reasons. They feared it would damage their impartiality and potentially drag them into international conflicts. Furthermore, Switzerland was not, at the time, a member. He also wanted Liechtenstein to join the EEA in order to maximise its worldwide export opportunities. Over the course of several years’ intense campaigning, Liechensteiners voted to join the UN in 1990 and the EEA in 1995, as well as the EFTA in 1991 and the WTO in 1995.

Prince Hans-Adam II (1945-)

On the constitutional side of things it was clear that the balance between prince, government and people needed attention. All constitutions change over time as interpretations evolve and in the prince’s eyes political discourse had become increasingly influenced by republican-esque ideas which undermined the dualistic nature of the 1921 constitution. He had no intention of allowing the monarchy to be deprived of real power and being reduced to a merely representational role. Following intense debate, the people voted two to one in favour of his proposed new constitution which strengthen the position of the monarchy whilst also strengthening the direct democratic element, as outlined in the last article. Opponents of the changes rallied a referendum in 2012 in an attempt to modify the changes to restrict the prince’s powers but this was rejected by 76% of the voting population. The other major controversial issue to come before a referendum during the last decade was the question of abortion. In 2011 a proposal to change Liechtenstein’s abortion laws in order to legalise abortion during the first twelve weeks of pregnancy or if the child were disabled was rejected by 52.3% of voters. Prior to the referendum Prince Alois had threatened to veto the proposal if it had been voted through. Thus it is clear that the prince still exerts considerable influence and authority over the political trajectory of the state. There is direct democracy in Liechtenstein, but it too is not absolute.

Hereditary Prince Alois (1968-)

One of the notable shifts over the last two centuries has been a closer association between the Princely House and the physical territory of Liechtenstein. Before future Prince Alois II visited in 1818 no prince had actually been there. On the eve of the Second World War, Prince Franz-Josef became the first prince to live in Liechtenstein. Since then, the Princely House has been firmly based in Vaduz.

When surveying the history of the Principality and its monarchy, one of the underlying themes is the importance of long-term strategic thinking. Throughout its history, and especially since the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and its successor confederations, the Princely House consistently advanced the sovereignty and independence of the state. To do so has required navigating the tricky waters of international politics through very difficult times, increasing prosperity whilst retaining a stable and harmonious sense of national identity and social coherence. The modern era has been particularly unforgiving for monarchies wishing to retain power and influence. Many monarchies across the world collapsed and disappeared during the twentieth century. In this regard, smallness has served Liechtenstein well and arguably allowed the monarchy to do things which would be much more difficult if not impossible in larger monarchical states, particularly in the west. But the emphasis on the long-term illustrated by Liechtenstein does represent a peculiar strength of monarchy as an institution when done well.

Recommended reading

For highly readable and comprehensive histories of Liechtenstein and the present monarch I strongly suggest two books by David Beattie, former British Ambassador to Switzerland and Liechtenstein: Liechtenstein: A Modern History (Schaan, 2004) and Hans-Adam II Prince of Liechtenstein: A Biography (Schaan, 2020).