In the chapter on ‘The Imperturbable British’ in Luigi Barzini’s 1983 book The Europeans there is an interesting theory as to what once made the British so successful. The nineteenth and early twentieth century had been a time of pervasive Anglomania and the country’s obvious success provoked admiration and envy in equal parts among observers abroad, something which lingered for some time after. For foreigners like Barzini, getting to truly understand the British mind was a difficult task, he reported, since the sorts of British people he mixed with, i.e. the ruling classes and successful middle class, had been bred to not talk about a whole litany of subjects in a social setting: “As they were forbidden to talk about themselves, their families, personalities, children, servants, the things they did, the things they knew best, religion, and politics, they were therefore limited to noncommittal generic statements and vague banalities.”

So how did Barzini get to understand them? He recounts how a friend, Bernardo, who happened to be half British (on his mother’s side) and half Italian, cautioned him that he wouldn’t be able to form any valid conclusions since “the English behaved in a particular way when there were foreigners present.”

Over the course of many years, however, Bernardo had apparently conceived of a theory as to how the English worked, and by extension, what made England work. The key thing was not intelligence in and of itself but rather knowing how to behave intelligently when the need arose. He explains:

“They all had a few ideas firmly embedded in their heads. He said “seven ideas”, but his figure was probably too low. Whatever the number, the ideas were exactly identical and universal. That was why in the older days, in distant lands with no possibility of communicating with their superiors, weeks or months by sailing ship away from London, admirals, generals, governors, ambassadors, or young administrators alone in their immense districts, captains of merchant ships, subalterns in command of a handful of native troops in an isolated outpost, or even ordinary Englishmen, facing a dangerous crisis, had always known exactly what to do, with the certainty that the prime minister, the foreign secretary, the cabinet, the queen, the archbishop of Canterbury, the ale drinkers in any pub, or the editor of the Times would have approved heartily, because they too had the same seven, or whatever, ideas in their heads and would have behaved in the same way in the same circumstances. He mentioned Fashoda as an illustration. Kitchener did not have to ask anybody what to do when Major Jean-Baptiste Marchand arrived. He raised the flag (the Egyptian flag in this case), risking a war with France, possibly a European war. The fact that the British knew they all had the same “seven” ideas in their heads made it possible for the authorities in London to trust the men on the spot blindly, those who surely knew more about the local situation than anybody else.”

How did this all work? The key lay with the elite, “the quintessence of Britishness”, who were the leaders of the nation and who were open to new talent in each generation, but were primarily formed of people who were related to each other or related to relations and had thus known each other from the earliest ages, gone to the same schools and universities, were on first name terms with each other and spoke with the same accent. The seven ideas were inculcated from nursery age and later in the classrooms and on the playing fields of the public schools. However, “all other Britons of all classes shared the same ideas, absorbed in childhood from the parents at home, from ministers in church, and from the teachers in whatever school they went to.”

We are not told what these seven ideas actually were. It doesn’t particularly matter. The important thing is that people were taught how to think for themselves in pressing situations, not to simply defer to authority. After all, authority is not always present and said authorities had to be able to trust subordinates to make the right decisions. This all worked very well until it didn’t. Barzini states that at a certain point these seven ideas reached their expiry date. Certainly by the 1930s they were no longer applicable. The old magic was gone. He records an elderly Times correspondent commenting on the foreign policy crises of that decade, of Hitler and Mussolini and the threat of war, to the effect that all these things were “signs of bad manners”. The old conception of politics and war as a game between gentlemen was gone.

Successful societies require capable leaders. Once the quality declines, not only does it become less likely that the code of honour and behaviour held by such leaders is transmitted undiluted to everybody else. It also becomes less likely that everybody else is inclined to follow. This also underlines the fact that real, effective leadership is not something which is taught at ‘leadership seminars’ or courses. It can no more be created on command than you can wave a magic wand and bring back the culture of Victorian England. It is imbued through an organic, cultural atmosphere which develops slowly over time.

To reiterate, the key to Bernardo’s “seven ideas” is not raw intelligence, but knowing how to behave intelligently. This is important. While they have produced some very gifted intellects, as a whole the English have never been a nation given to intellectualism. The education of the elites of nineteenth and early twentieth-century Britain prioritised sports and games and competition, and a general reading of the classics, over bookishness. Action was more important than abstract thought. In different parlance, it was a society run by chads not nerds.

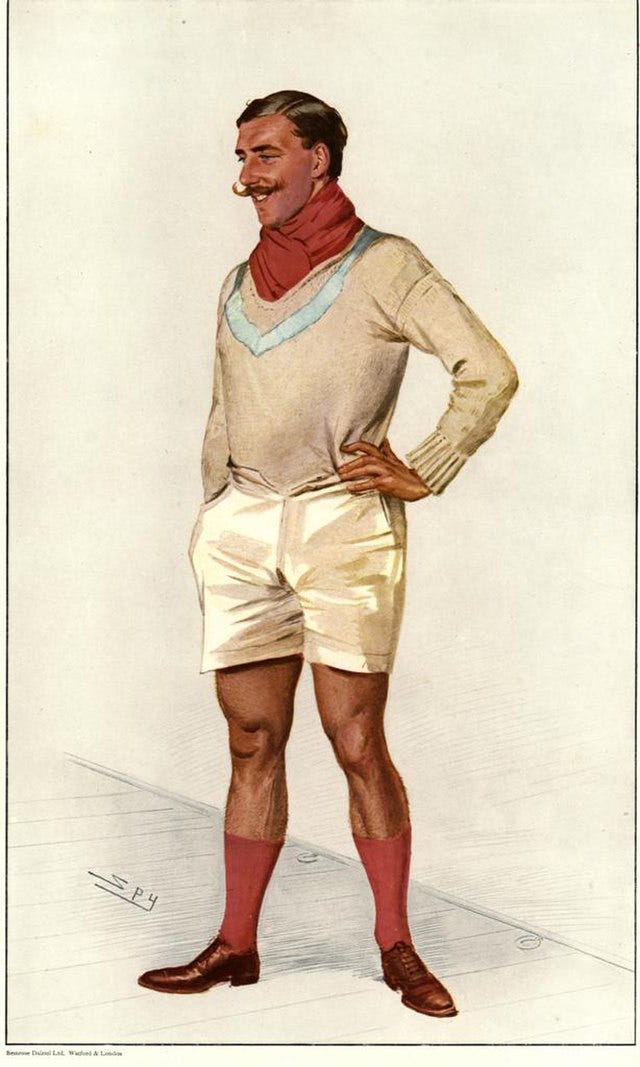

Olympic rower Banner Carruthers Johnstone, pictured here in 1907 by the cartoonist “Spy” for Vanity Fair. Carruthers later served in the Ceylon Government Surveys, the Colonial Civil Service and the army. For his military services with the 1st Black Watch and the 1st Infantry Brigade during the First World War he won an OBE. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

This post originally appeared in April 2024.

An interesting idea. I think the line "...code of honour and behaviour held by such leaders is transmitted undiluted to everybody else" tells us more than anything else. I believe this would qualify as social norms. At least in part. It is understanding what society expects, permits, and values.

"England expects that every man will do his duty" is vague but in a society with a common understanding of the term "duty" it is enough for the men to know what it means. Kitchener knew to raise the flag because honor and duty expected it.

Social norms are not just transmitted from leader to citizen though. There's a feedback loop in democracies. Once citizens permit social norms and values to slip, immoral (for lack of a better word) leaders become more likely to gain power. They are seen to have been rewarded for what was, until recently, bad behavior, and more in society will excuse and adopt that behavior.

The "slippery slope" theory played out in real time.

The decline of leadership in the 1930s was caused by WW1. War causes inverse evolution...survival of the least fit. Almost all of the future elites died on the Somme and similar places. Many of those who survived (Graves and Sassoon are good exanples) were broken.

The result of the slaughter was that the leadership class of Britain was immediately contaminated with imbeciles, buffoons, narcissists and other low quality human dregs. WW2 completed the destruction of the british elite, and the new post war rulers, being as thick as two short Gurkhas, quickly destroyed the country.

And here we are now. Look at the current Parliament from the PM down. They should all be shot, pour encourager les autres.